A new lawsuit recently filed by a local union might be overlooked as just another dispute over money. Â But what makes the case noteworthy is the fact that unions rarely air their dirty laundry in public–especially when it involves the alleged misappropriation of the union’s money.

The Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 1107 represents a number of Clark County employees including those working at UMC, the RTC and the LVCVA. Local 1107 sued its former President, Chief of Staff and Financial Officer for the alleged conversion and misuse of over $47,000 in union funds. The union also seeks punitive damages in excess of $140,000.00. You can read the lawsuit here.

It’s pretty serious stuff for a union to sue one of its union “brothers†or “sisters†just because they allegedly compensated themselves too well. Wouldn’t it have been easier and less embarrassing to just sweep it under the rug—especially when this particular union took in nearly $5 million in dues last year and on December 31, 2013 had nearly $300,000 in cash on hand?

Well, either the current leadership of the union was intent on doing the right thing or perhaps the union felt it had to go after the money because its finances are subject to public scrutiny.  SEIU Local 1107 is one of the few public employee unions that also represents employees in the private sector—notably most of the large for-profit hospitals in town. Because it represents private sector employees a federal law, the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA), regulates it.

Congress believed unions needed regulation for a very good reason. “Like any functioning organization, a union must make financial decisions on a constant basis. The ability of the union to perform its representational functions depends on the availability of sufficient financial resources. Also, like any other institution, concentration of authority over the management of money entails the risk that authority will be abused. Unlike their commercial counterparts, unions do not have a tradition of hiring financial experts to manage their affairs. Workers who have had no financial training before their election to union office become, upon election, responsible for managing funds and property in amounts beyond their experience. As one court has acknowledged, union officials ‘are neither accountants nor controllers: Their positions as union leaders demonstrate their organizational rather than financial expertise.’â€Â Labor Union Law and Regulation (2003),William W. Osborne, Jr.(Editor).

Â

That is why in 1959 Congress passed the LMRDA, which imposed, among other things, an obligation on unions who represent employees in the private sector to file annual financial reports with the federal government. You can see SEIU Local 1107’s most recent report here.  The federal government does not have the ability to regulate unions that only represent public employees.  Regulation of public employee unions are left to the states.

So therefore, what do the hundreds of members of other Nevada public employee unions know about where their dues money goes? Nothing.

There are some small pockets of Nevada public employees who are represented by unions subject to the LMRDA, for example: Teamsters (Local 14 in Las Vegas and Local 533 in the North), International Union of Operating Engineers (IUOE Local 501 in Las Vegas and IUOE Local 39 in the North) and of course the International Union of Elevator Constructors Local 18. But the vast majority of Nevada public employees (and the Nevada taxpayers in general) are entitled to no information whatsoever on the how the unions handle their money. Â Keep in mind that the large police and fire unions handle massive amounts of dues money and some own substantial buildings and land.

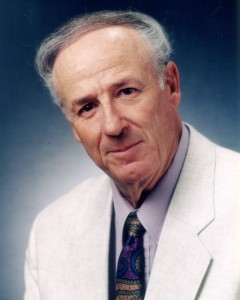

To uncover how a Clark County teachers’ union chief got paid  $632,000 in compensation in one year a lot of digging was necessary—read about it here. In the rare case there may be a press report on some internal financial impropriety like this: “Case against ex-head of police managers union closed quietlyâ€.   You can tell by the headline itself that the union wanted the public (and maybe the members) to know nothing. That story was reported by Jane Ann Morrison. Sadly, Morrison retired this past Labor Day and only a few in the press can dig so well.

Other states have dealt with the problem of invisible union finances by passing a state law similar to the LMRDA. Alabama, Kansas and South Dakota require public employee unions to file annual financial reports with the state. Minnesota and New York require the unions to give an annual financial report to their members.  The states use various enforcement tools from barring an offending union from collecting dues to fining the union’s officers.

Shouldn’t Nevada’s public employees have similar protection? In 2011 Assemblyman Mark Sherwood courageously proposed Assembly Bill 105. The bill only required the unions to prepare an annual financial report and “make it available for inspection upon request†to any member who paid dues in the prior year. Of course it would have been better if it required public filing of the report like the LMRDA. The bill also lacked a good enforcement mechanism. But at least Mr. Sherwood tried to do something. Not surprisingly the bill never made it out of committee.

You can expect the unions to complain that finances are an internal matter that does not involve the employer, the taxpayers or the public. But doesn’t the handling of dues money impact the public? After all, the local government payroll systems used for dues deduction is owned and operated by the taxpayers.

Also many unions have the right to use local government space for union meetings, and to use local government email systems, or local government wall space for bulletin boards. Doesn’t that taxpayer provided free stuff permit unions to use dues money for other things? Shouldn’t unions have to account to the local government how well they are safeguarding and using that dues money?

Plus what about the union business time that many local governments pay for? Shouldn’t the taxpayers be able to see how the dues money is being spent? Maybe through better spending habits or by safeguarding against theft there would be plenty of dues money to pay for all of the business that unions do. Then the taxpayers wouldn’t need to pay any employees for union business time—what a novel concept!

Perhaps in the coming legislature some brave legislator will try again to require some accountability from the public employee unions.